Apart from seeing my Dad – this museum was one of the principal reasons I had come to the UK. (Turing’s influence on Computing are diverse – and I had read a great book on his PhD.)

I did spent six hours walking around, there as there is a lot to see and take in, a full day. The museum has intersecting themes here, of military history and significance, code-breaking, and development of computer technology. It’s big focus is people, and their experience of being on the code-breaking site.

I have written pages and pages of notes, and taken hundreds of photos during the day – but I’ll keep this brief.

The Mansion was built in the 1880s by a wealthy stockbroker, and his children sold it during WWII to Admiral Hugh Sinclair. It was purchased for its equal proximity to Cambridge and Oxford (they had a train line called Varsity connecting them at the time) and London.

People’s Experience

There is an enormous sense of careful stewardship of resources.

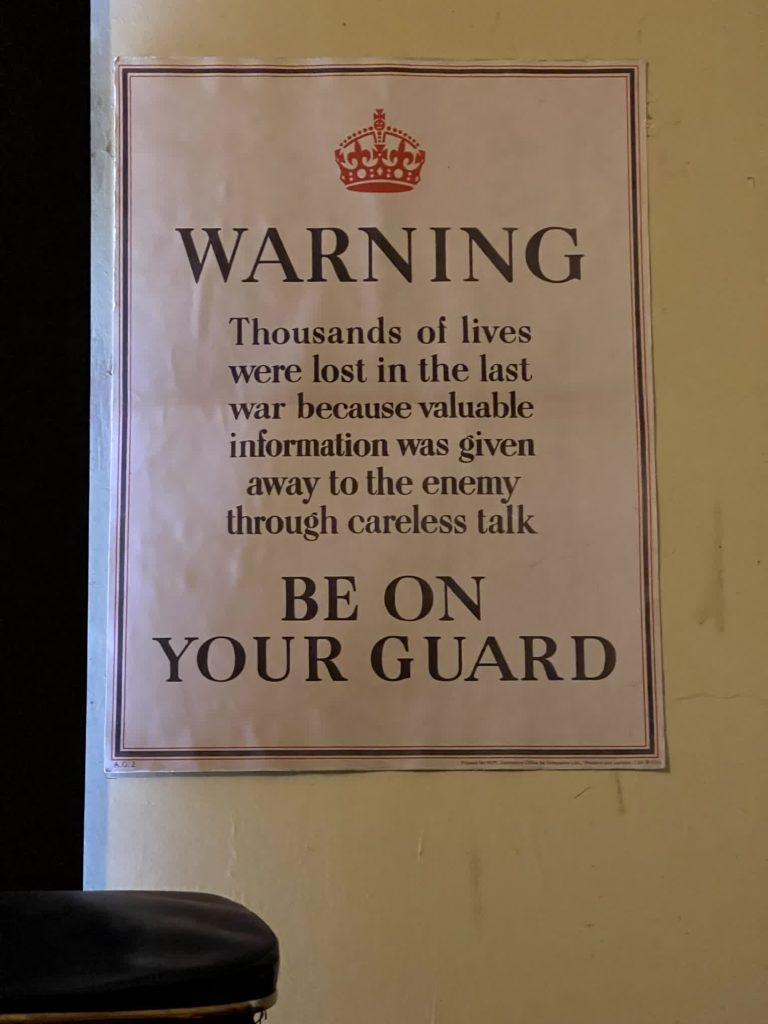

Of the moral obligation to keep secret due to the failures during WWI of spies listening into plans.

Signs at desks reminding people to “Keep At It!” that hint at the drain on people during the war. Stories of nervous breakdowns, and the the need for tennis matches, Scottish Dancing, Operatic Performances and Fencing Clubs.

Cracking Codes

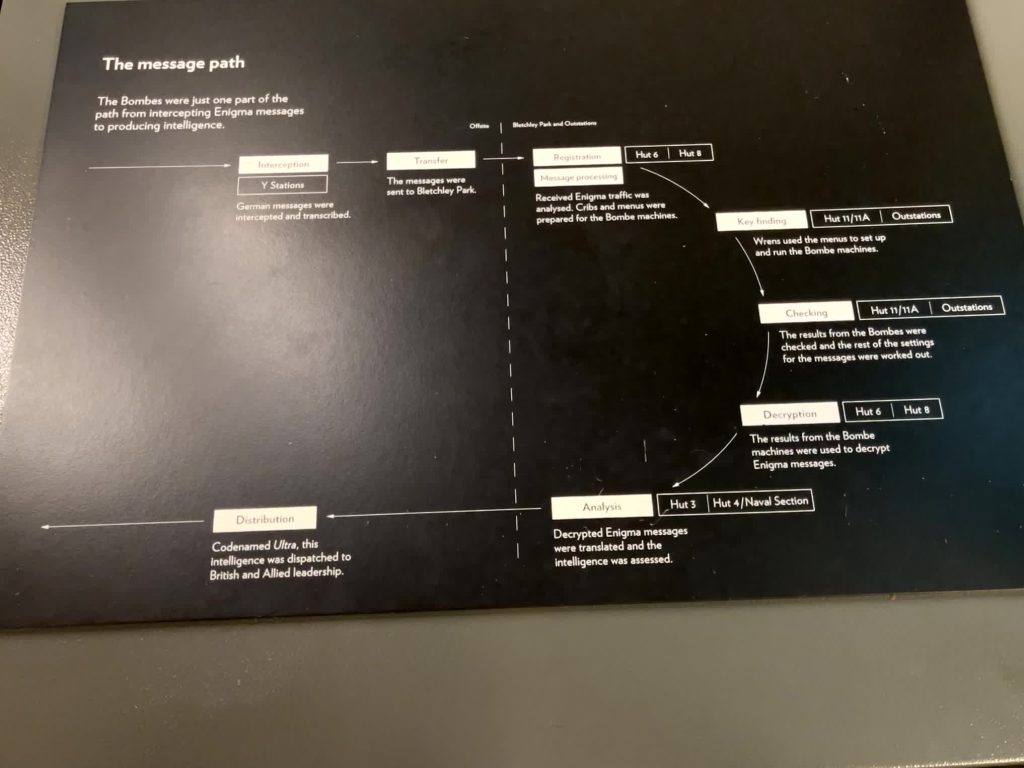

There was a multi-step system for cracking codes that came in during the day.

The motor bike riders delivering messages skills in Morse code, repairing motor bikes, map reading, operating a sub machine gun, laying field cables from moving trucks. They were instructed to have zero curiosity about the message except where it was being carried.

In 1940 they removed the road and railway signs to confuse a potential invading enemy. Some riders chose to vary routes in case they were being followed. Some had to drive around bomb debris in London.

The riders could ride up to 1200 miles per week sometimes at night, dealing with ice and snow. The riders wore blue and white armbands identifying they were not to be held up by military patrol, and could ask military vehicles for petrol.

Victory – VE Day

The Park had been storing information on punchcards, as a storage and retrieval system. When Victory was announced, the girls threw all the cards up in the air!

History of Development of Codebreaking

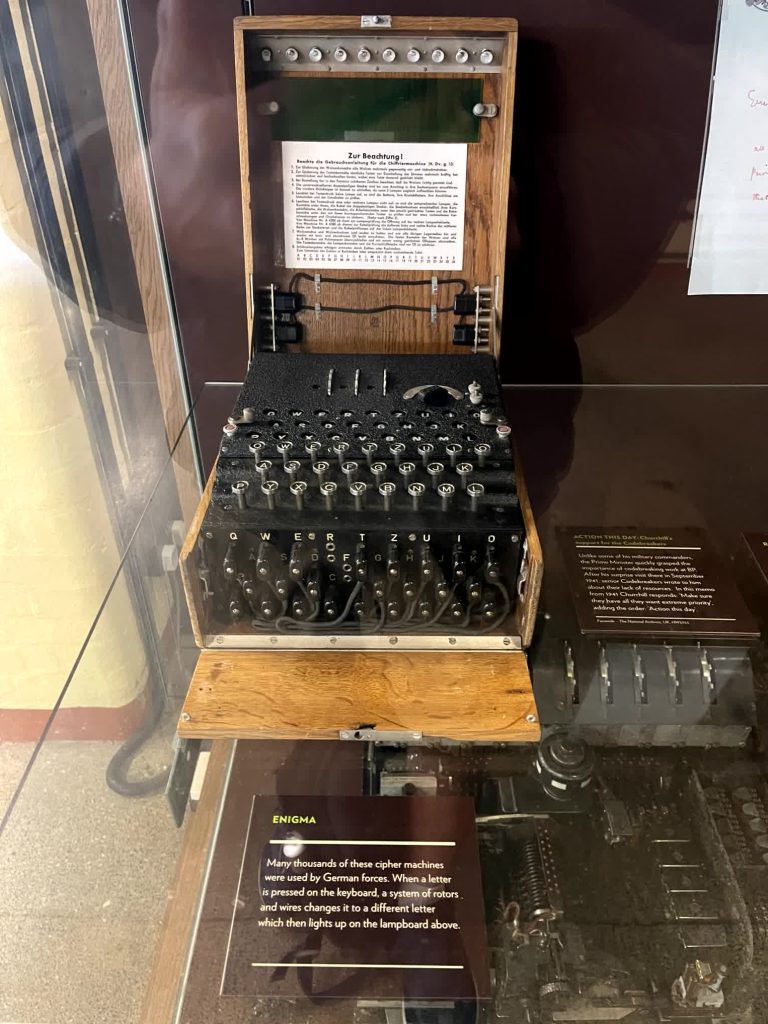

The Enigma machine had been developed by a German electrical engineer Arthur Scherbius in 1920. The (3-rotor) machines were common knowledge.

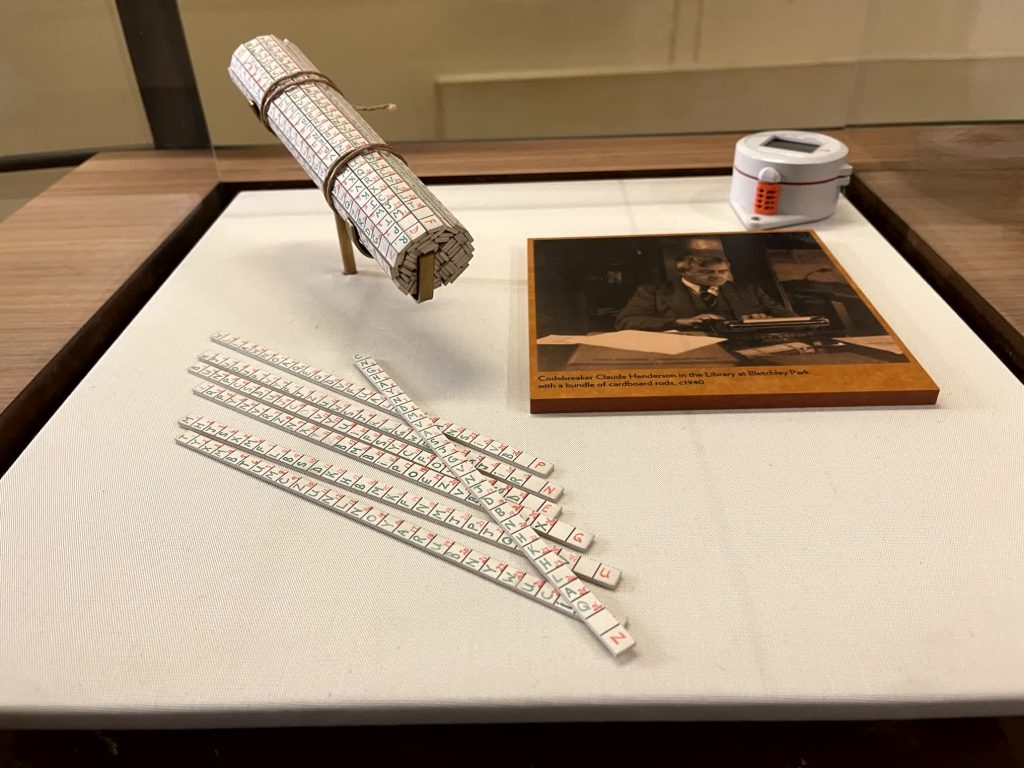

An English Mathematician had developed a system of cardboard strips to break Enigma codes. The challenge was with rotating settings and different plugboards, you had to keep re-cracking the day’s codes.

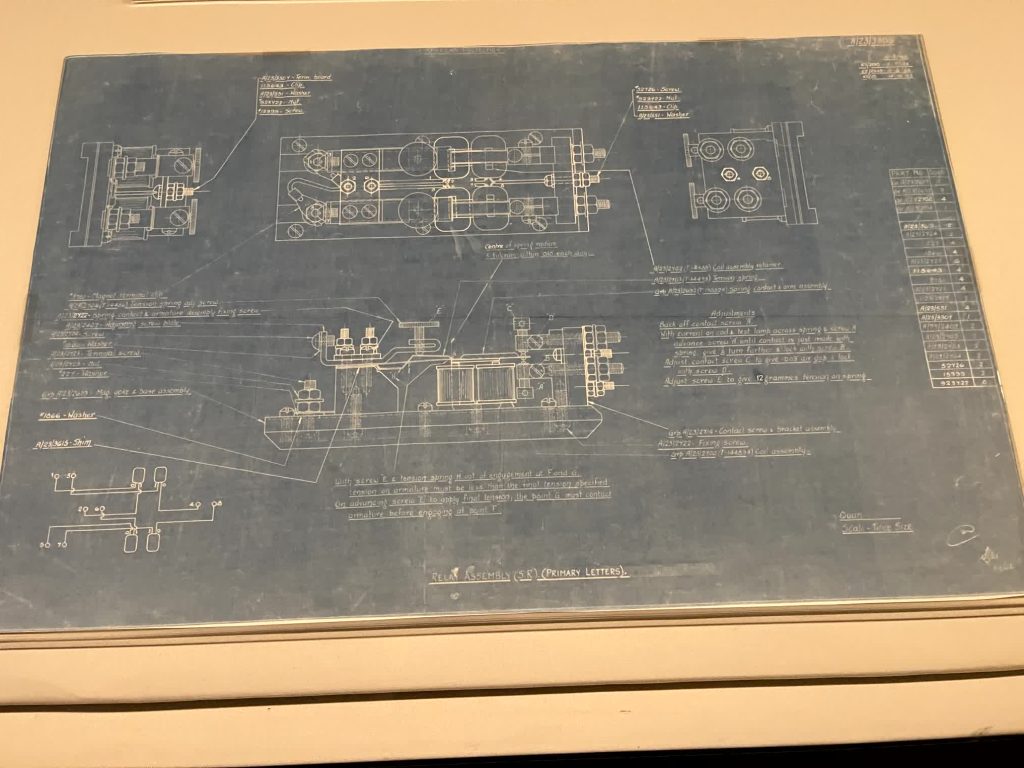

Turing had started work cracking Enigma codes as soon as WWII broke out. He wrote a detailed description of how it worked (he showed remarkable Engineering capabilities).

The Germans increased the choice of rotors in the Enigma – choosing 3 from 5 and inserted in any order. This made cracking the codes more difficult.

(Enigma Rotor)

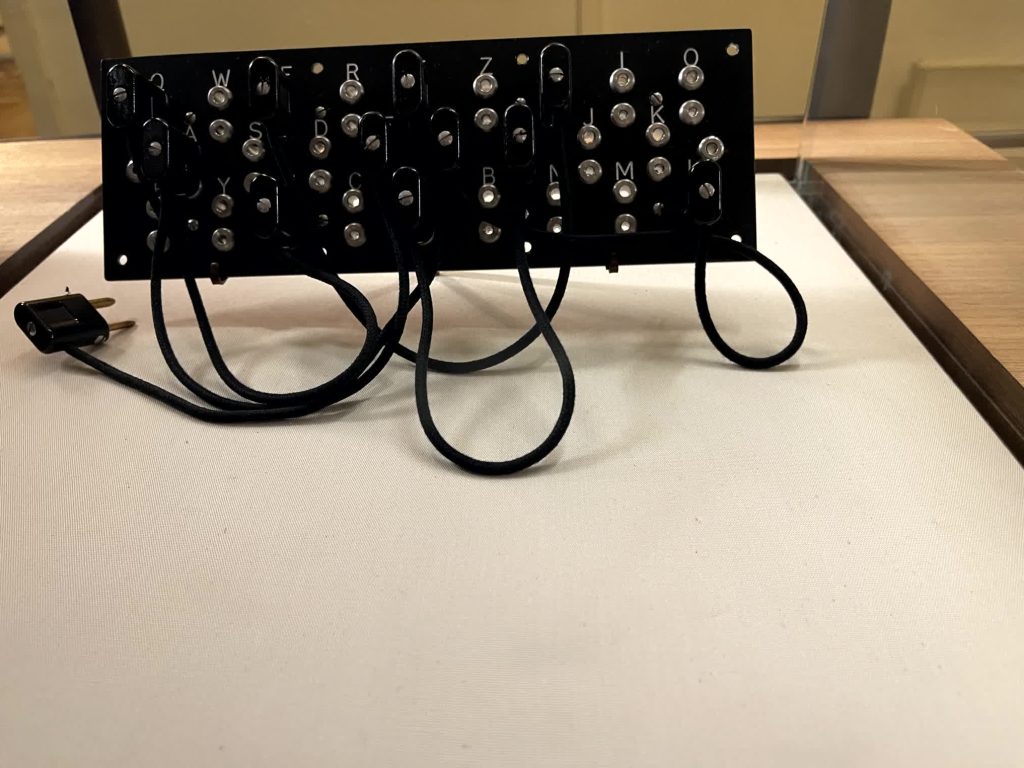

The Polish developed a system of plugboards that had some effect for decrypting enigma codes.

Later the the Polish developed The “Bomba” (in Polish – something special – like icecream) to cycle through rotor positions. This had some effect to crack enigma codes).

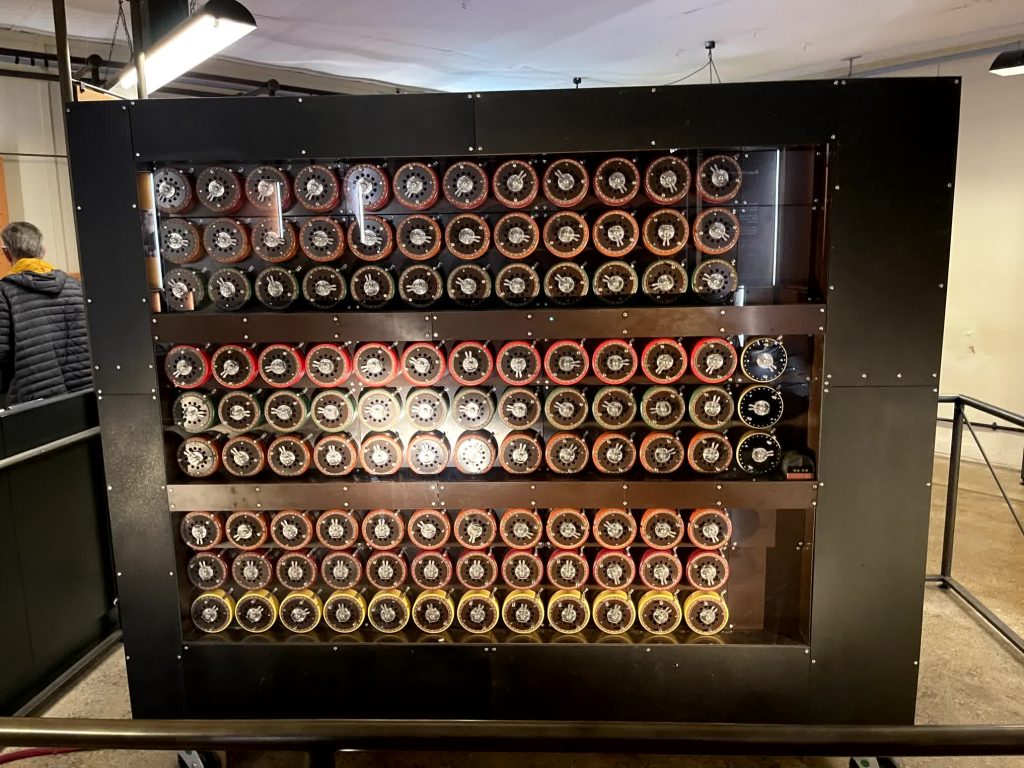

Turing did a design for breaking Codes – called the Bombe machine.

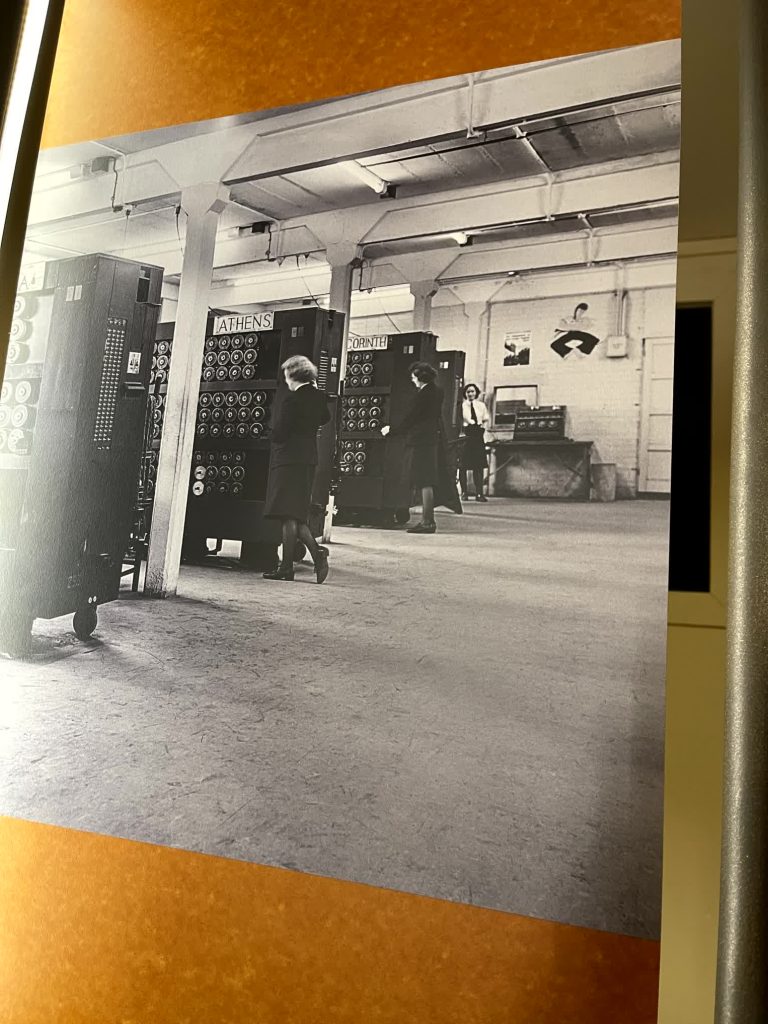

This was built, and hundreds like it by the English and Americans, and they were run 24 hours a day. (The cigarette smoke was detected in the walls from the operators.

They had a model running (since all the originals were destroyed after the war.)

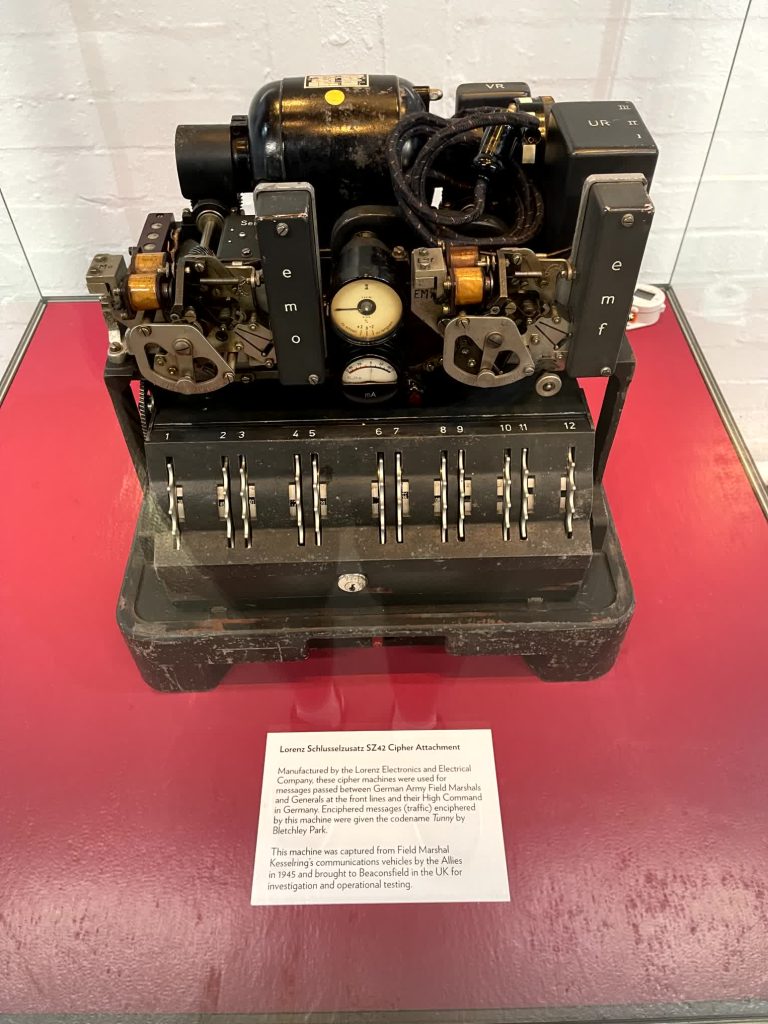

Hitler used a more secure machine called Lorenz for communications to Commanders. This was broken using a new machine called the Colossus. This is significant for signals intelligence on D-Day. (more on the Colossus tomorrow).

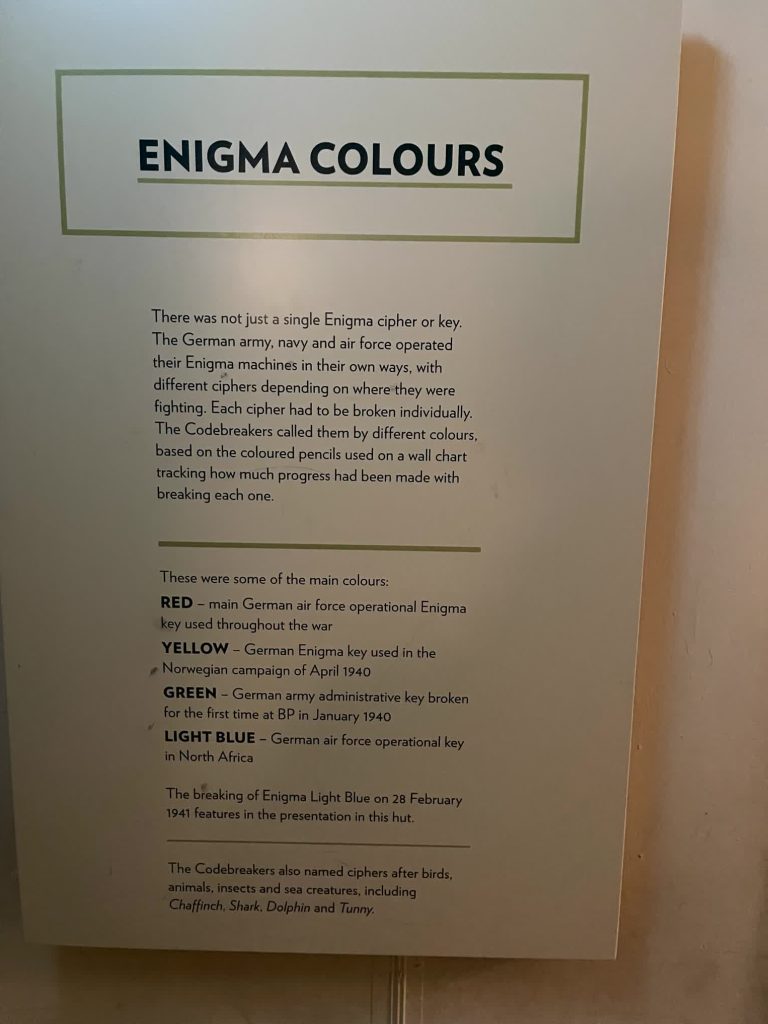

Enigma Types

There were many different types of enigma: