An offshoot of the Bletchley Park museum, which leans more towards military stories, this Museum is a place for the stories of Britain’s computer Industry following World War 2.

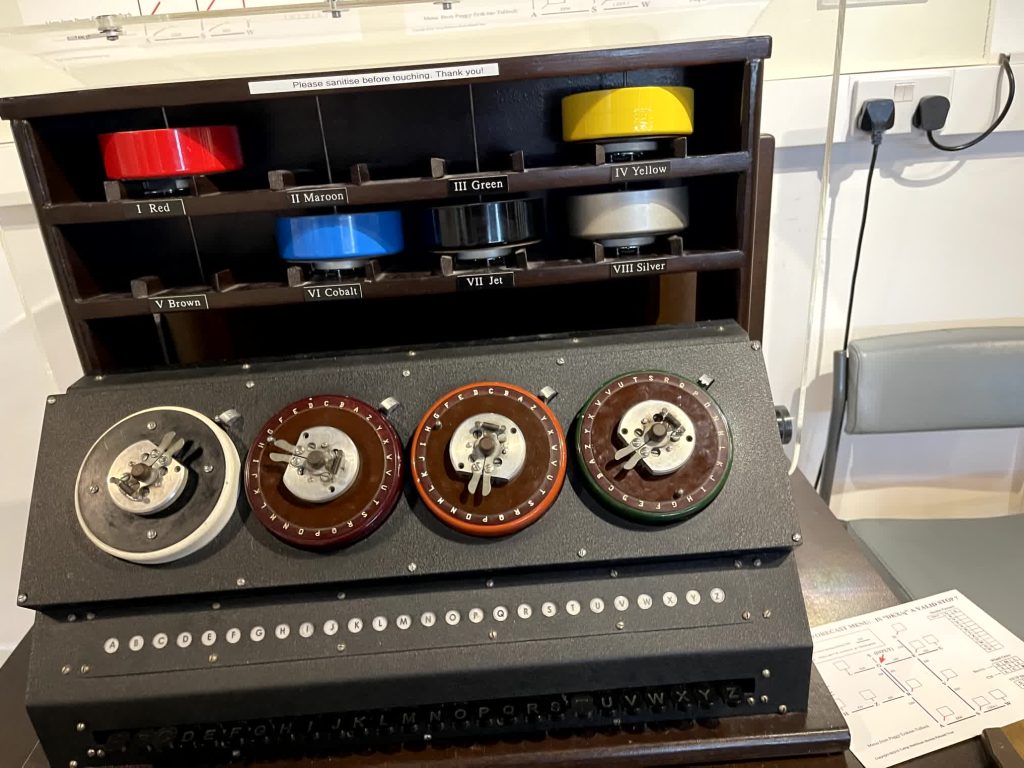

They start with a largely working Bombe machine replica – ticking over to find combinations that might work against a particular encrypted message.

Inside of a rotor, fine brushes made contact with the commutators. These were cleaned with tweezers by an operator. (This was modelled on the Enigma machine’s rotors).

The rotors were plugged into the commuatators:

On the back were plugs (26 pins for the alphabet) which were matched up to each rotor depending on the instructions for the run.

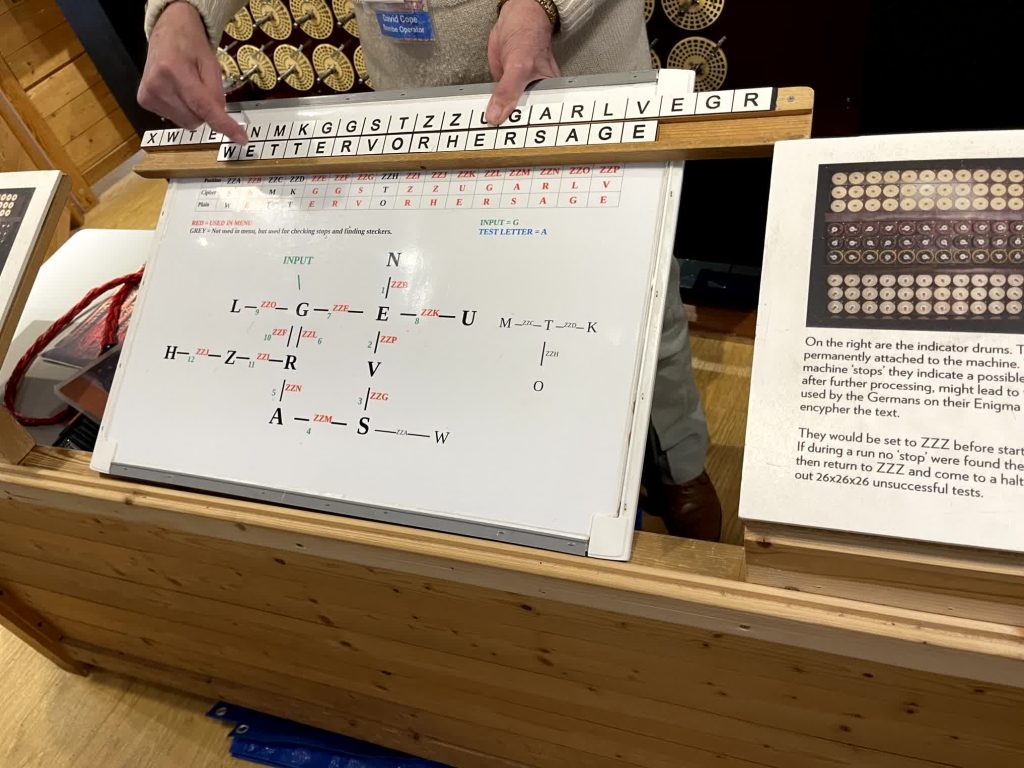

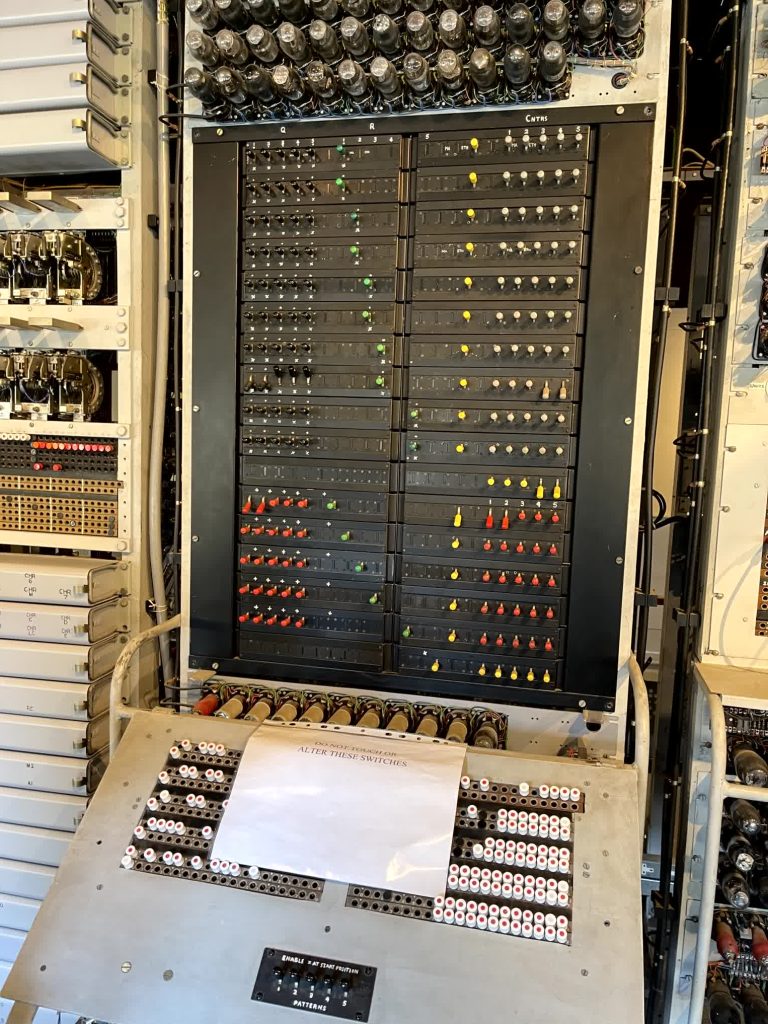

To choose settings for the machine – you would check for a crib (like the weather report) to check for letters not translated (ie the ‘W’ in the Weather Report would never be translated to W – so you could exclude that as a possible translation with a sliding rule.

After the Bombe had ‘stopped’ – you took it to a checking machine to see if you had hit a valid combination.

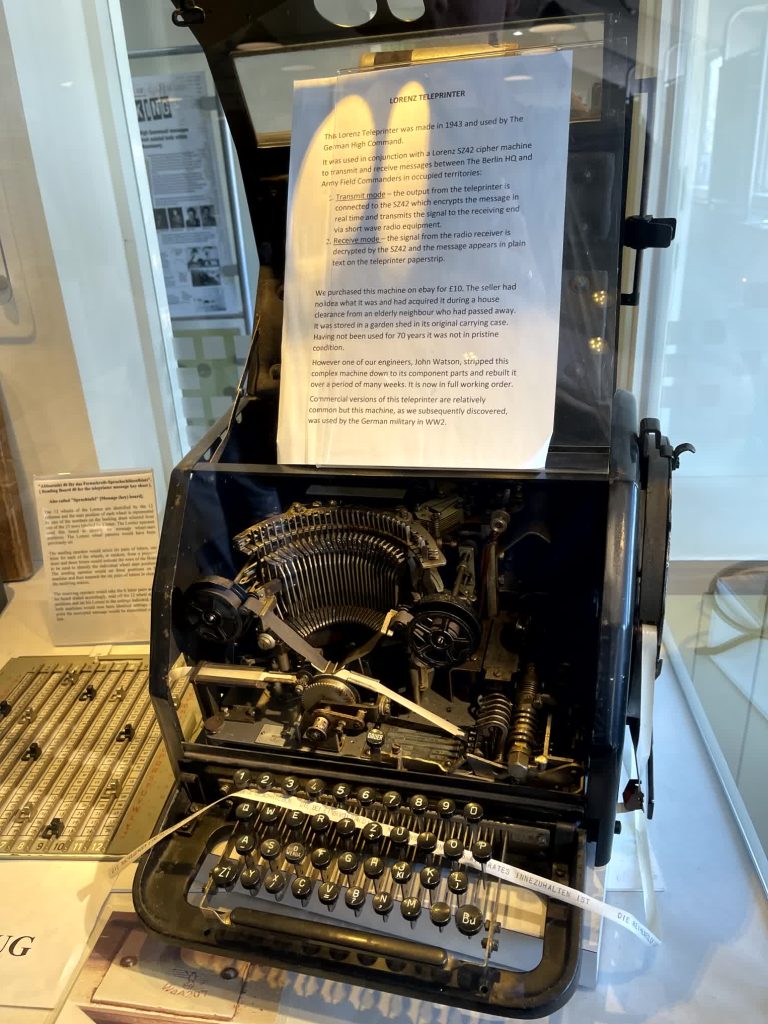

Next they had the Lorenz Machine and the machines for cracking it – a more sophisticated 12 rotor (instead of 3 rotor) machine the German high command used for overall strategy.

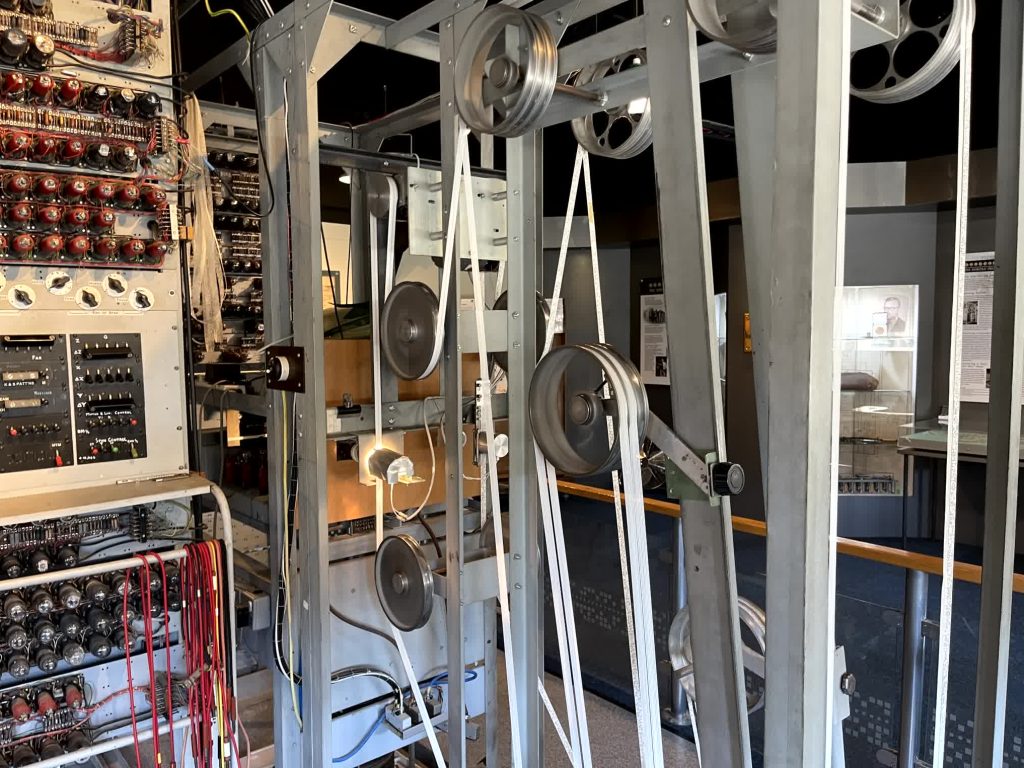

The first machine they attempted to build to crack it was named the ‘Robinson Machine’ – because it was considered an unreliable bunch of wires. It had two tapes, which were always getting out of sync with the machine.

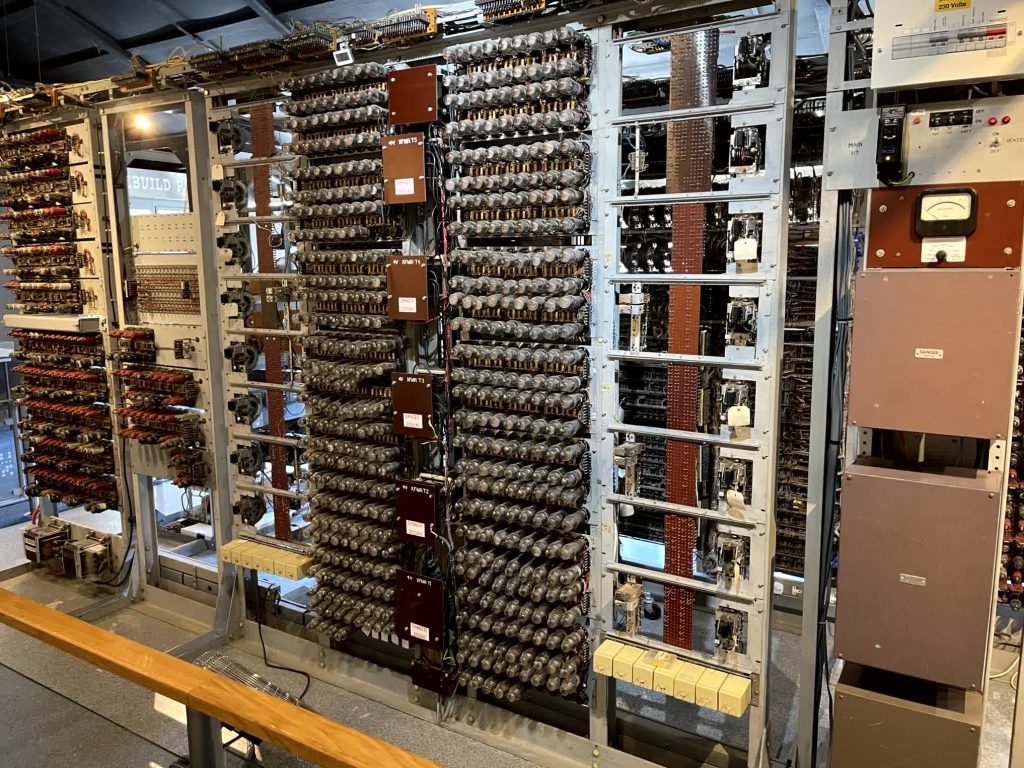

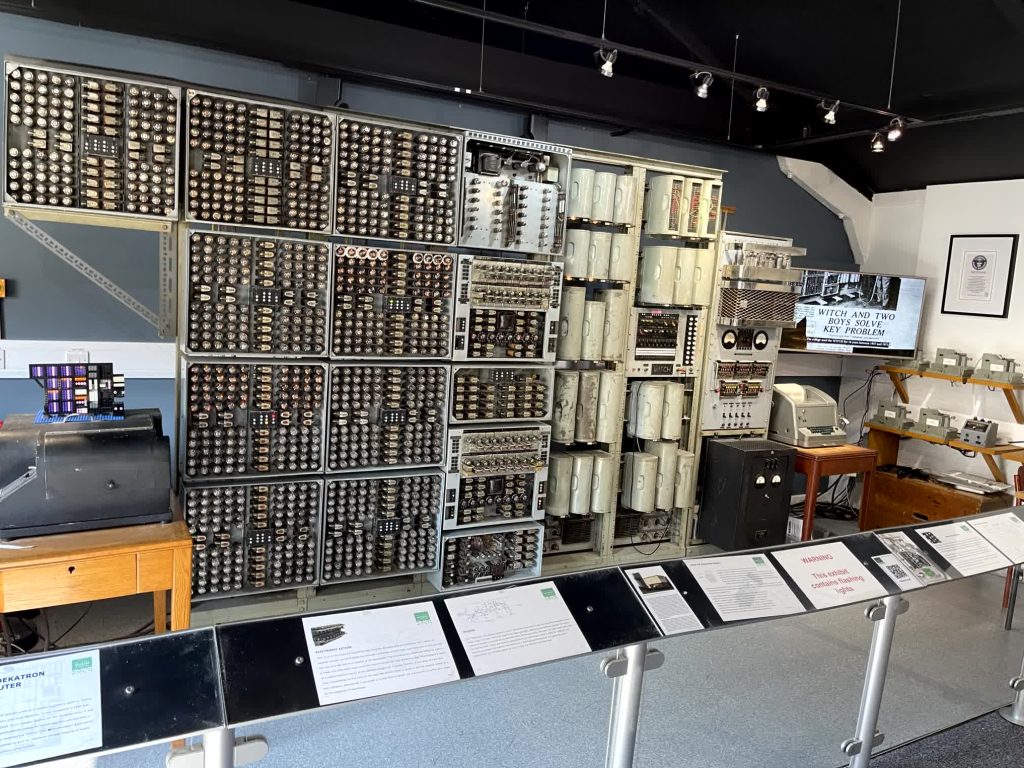

Their next attempt was the Colossus – built by people from the GPO who had worked on telephone exchanges.

It had a single rotating tape. (5 bits wide – one for each finger of your hand.)

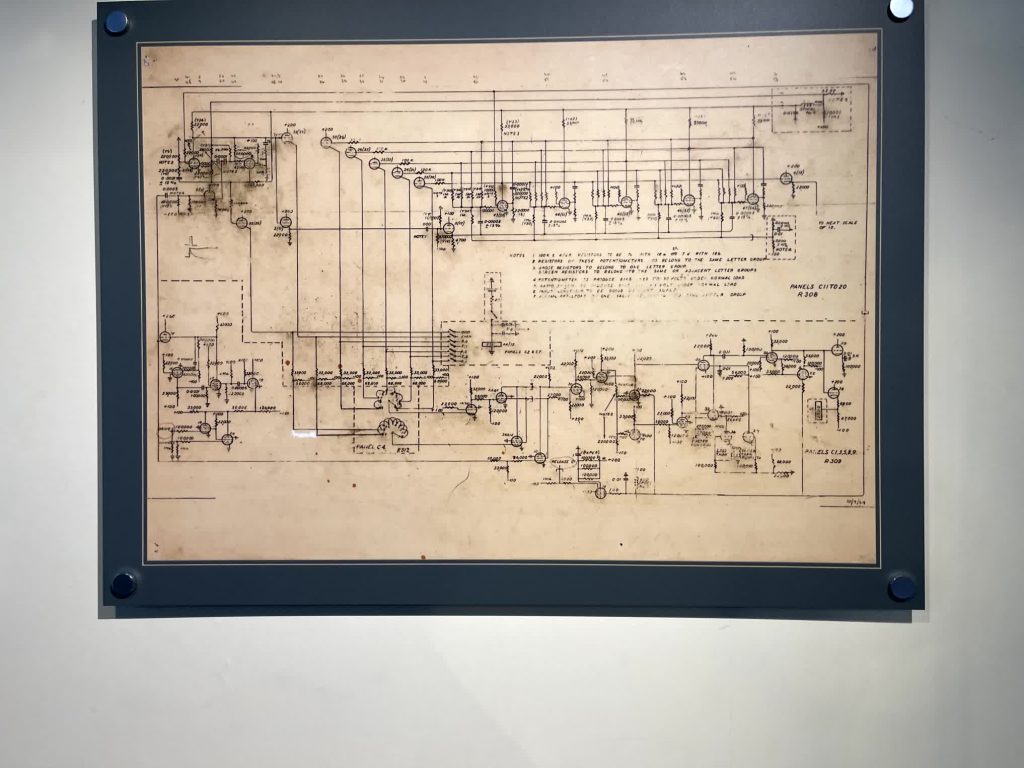

There is a philosophical question about whether it was truly the first computer. It had shift registers and branching instructions, but no memory. It was not general-purpose programmable. I am truly on the fence on this question. (It seemed like a bunch of electronics to do statistical attack calculations, looking for the ordered pattern in the randomness of encryption possibilities.) Still it is very close to Turing’s Phd thesis model of a Mathematical computer running on a tape.

The leaders of Bletchley Park at the time were so impressed with the first demonstration they commissioned 3 more on the spot to be delivered in two months. (The builders had spent 11 months working 12 hour days for 6 days weeks to deliver this prototype.)

Tony Sale did a rebuild of the Colossus in 1994 after working to save the Bletchley site from developers in 1991. He got notes from an Harry Fensom who worked on the original Colossus.

There is a profound historical parallel to the Biblical writings, where people don’t seek to preserve things by writing them down or publishing them, until or after the original people who experienced it were on their deathbeds roughly 40 years later.

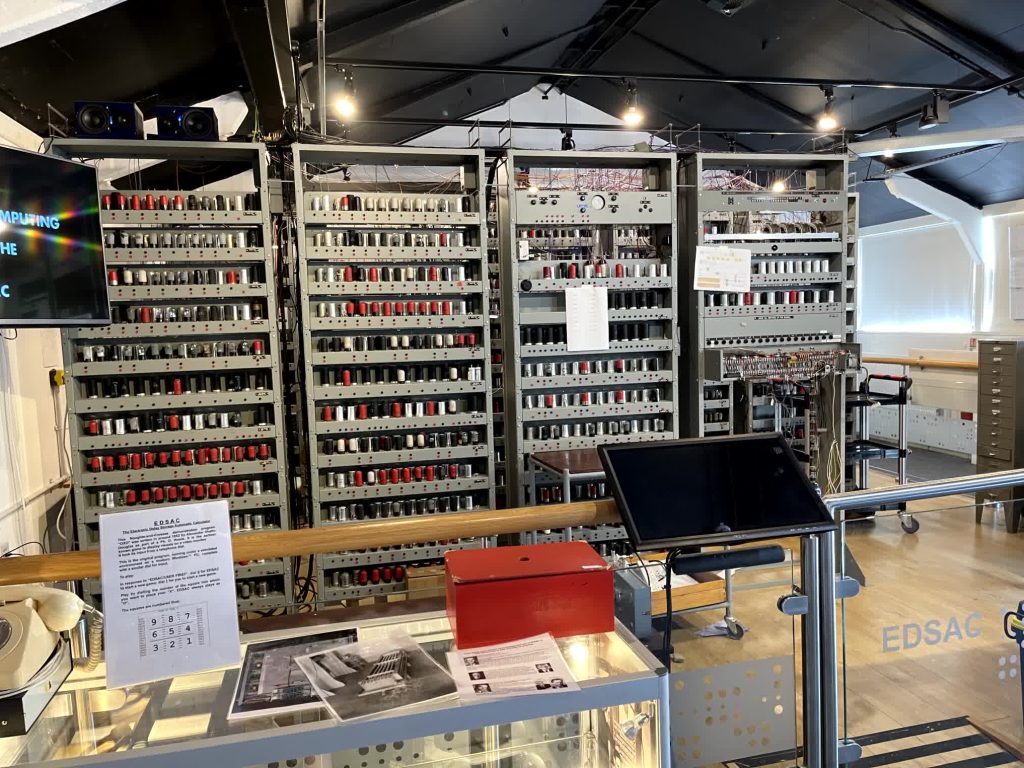

The museum also had a rebuild of the EDSAC computer. It was built for the Cambridge Math’s department. This was significant because it had Turing’s design for storage, a mercury delay line, and had a form of assembly language converted down to binary.

They had a Harwell computer, made from Geiger Counters (10 bit cathode tubes). A one-off given to a Maths department. It was as slow as a human at calculations, but but resilient and less error-prone. It was an early general-purpose computer.

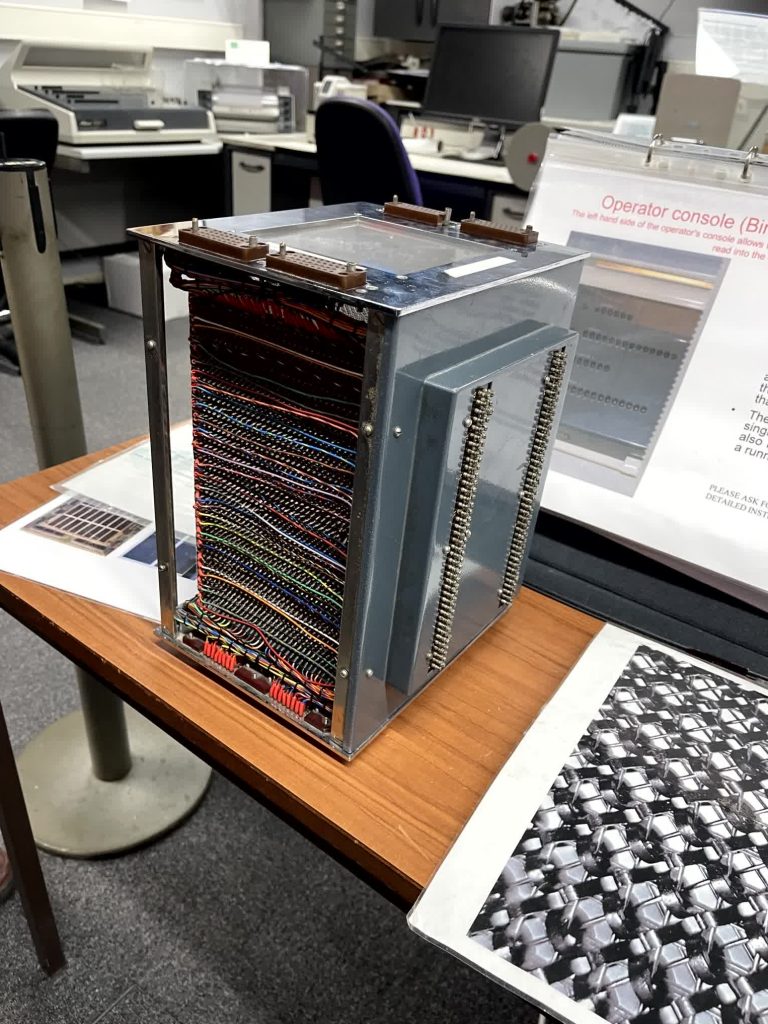

They had a mainframe memory core. From what we get our phrase ‘core dump’ still used in diagnostics today.

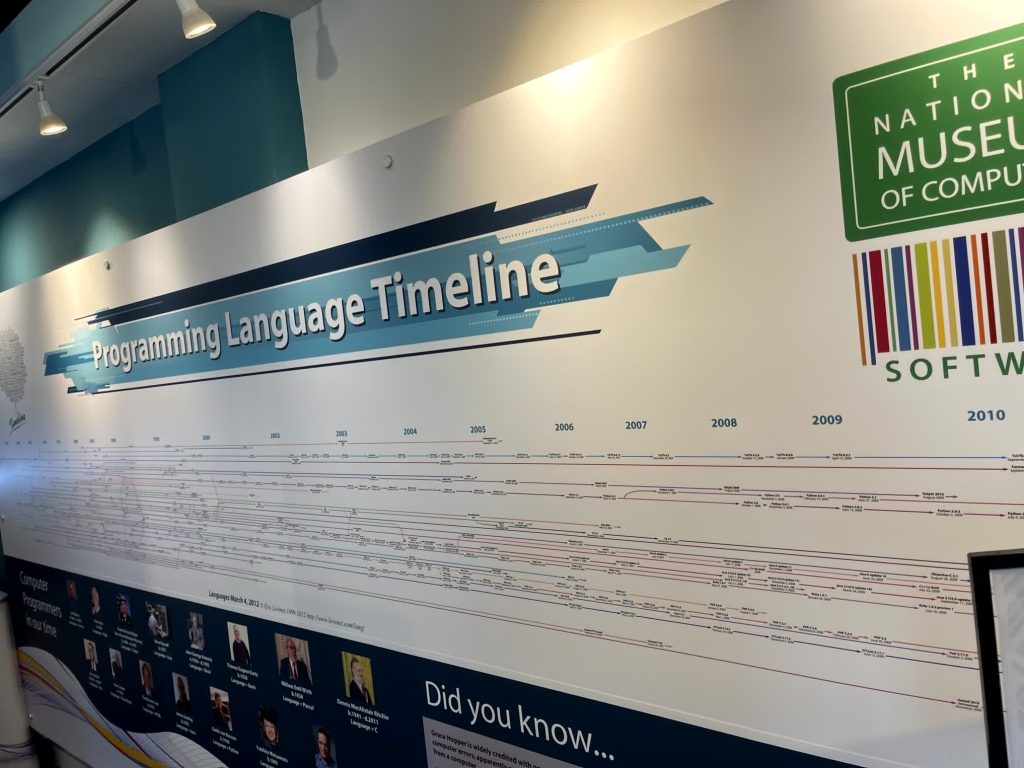

They had a software section with a programming language timeline.

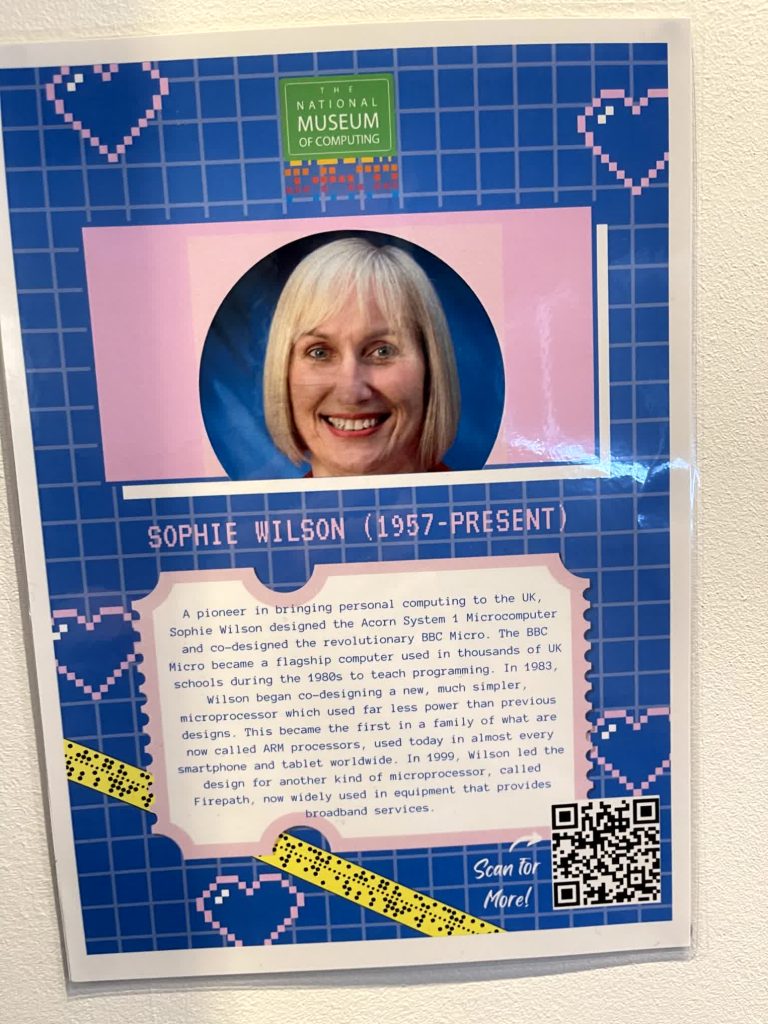

A note about Sophie Wilson, who designed the Acorn System 1, co-designed the BBC Micro, and was involved in the design of the first ARM chip.

Then they went onto personal computers. There was a Be next to a Macintosh.

They had a section on portable Computers, including a couple of Apple’s I remember from my childhood.

They had a section on the development of smartphones, including an Apple Newton and the original iPhone box.

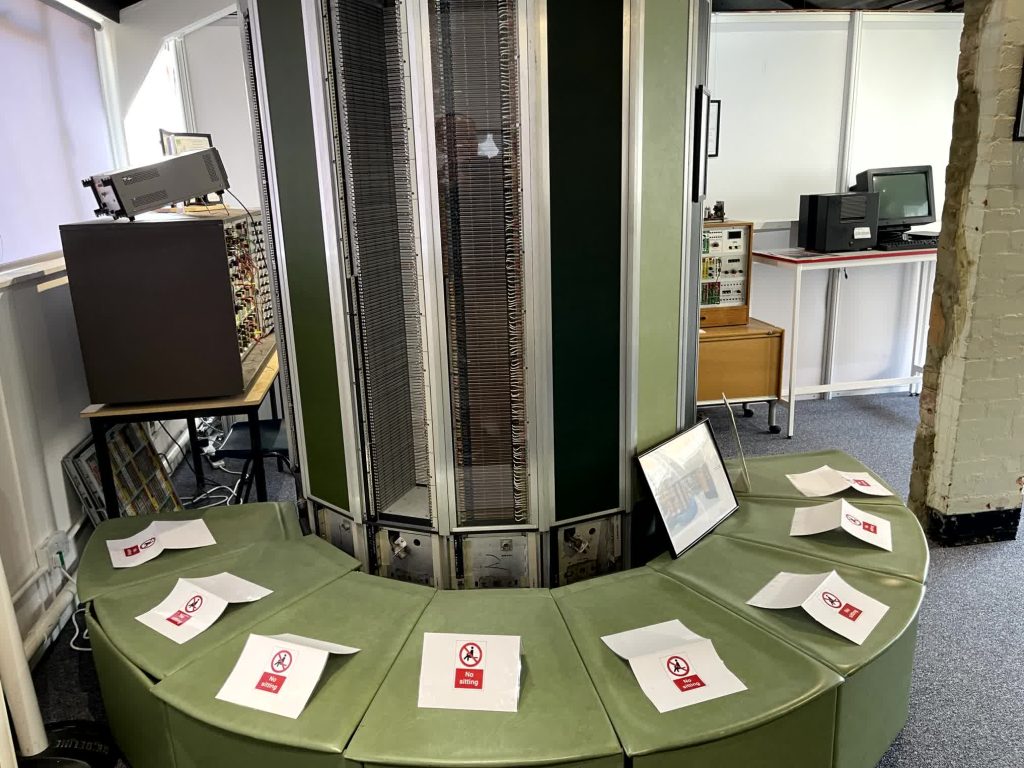

They had a Cray 1 Supercomputer from 1976. (Which my watch now beats in performance).

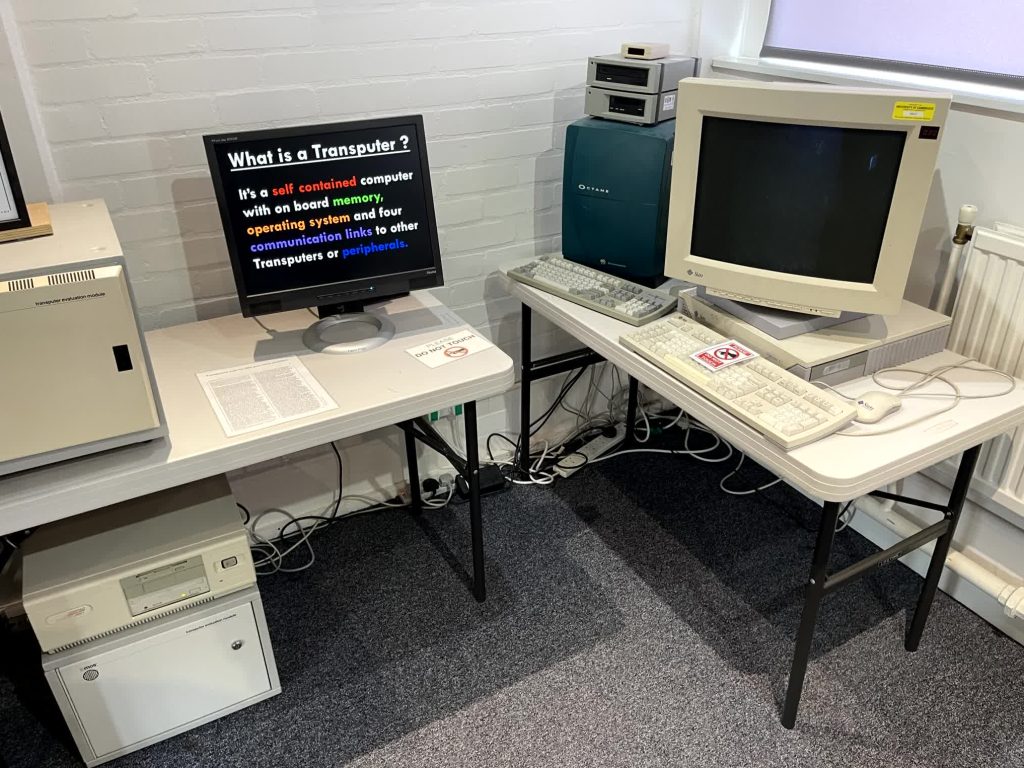

They had a Silicon Graphics workstation and a Sun workstation that I recall from Uni.

A driving club had come for a visit.

I recorded a train whizzing past (they seem to go faster here.) I estimated it was going about 145 km/h.

I couldn’t resist taking a photo of Rugby station.

My grandfather was born in Manchester and grew up grew up there. A manager at work once spoke with affection of the Manchester he grew up in. I wondered what it would be like.

The buildings around Manchester Piccadilly Station look like they saw the Industrial Revolution.

Whilst walking to my accomodation, I sat on a bench with Allan Turing. He told me my journey was nearly at an end.

Walking along the streets in the evening, people aren’t in a rush, many make eye contact and smile.

Walking through the streets on a Thursday evening big suites of tables from the pubs spread out into the streets, full of people talking.

At the Tesco buying dinner I asked a question and the attendant replied, “of course you can!” With a kind of sparky charm that hid the fact he’d been working on his feet for hours.

Manchester so far has come across as a compassionate, sparky and empathetic place. History tells me that not that long ago this is was a place of high unemployment. I imagine that in the post World War II childhood of my grandfather, this may have been a grim city.